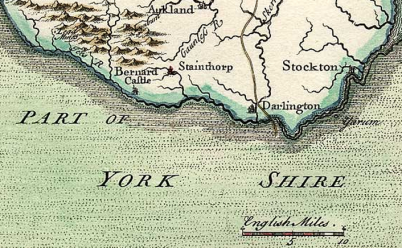

‘Stage Coachman’ by George Cruikshank, The Gentleman’s Pocket Magazine, 1827.

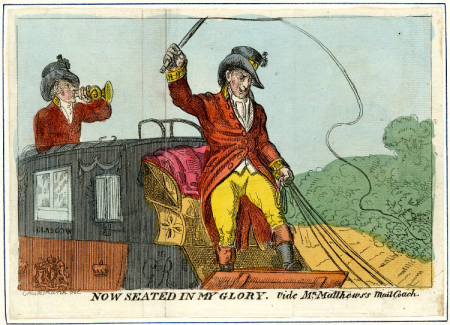

This post is about my five-greats grandfather Isaac Batten (1790-1843). A minor celebrity of his day, as driver of the London-Cambridge stagecoach ‘The Times’ he helped to establish the early 19th century stereotype of the big, fat, Cockney, hard-drinking ‘swell’ coach driver or dragsman; a popular stock character that later appeared in works by both Charles Dickens and Walt Disney.

After hanging up his coachman’s whip in 1840 Isaac became a publican, just like his fictional counterpart in the Pickwick Papers. The doors of his old pub in north-west Essex are still open today.

⁂

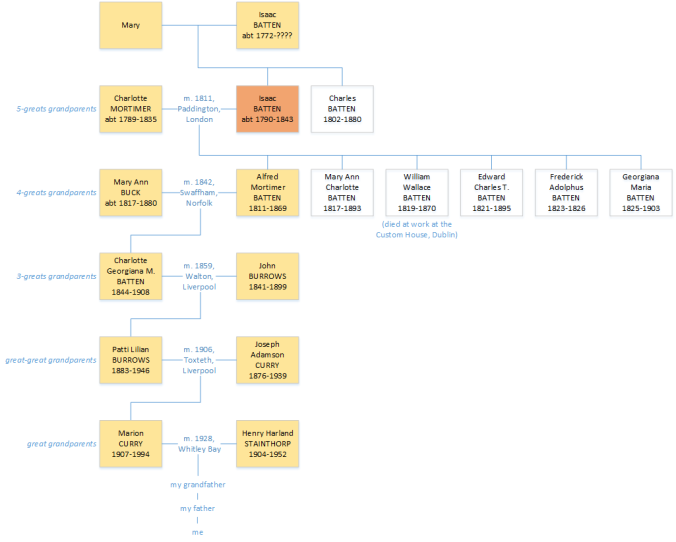

Isaac Batten was born circa 1790,(1) probably in London.* Although I have not found a baptism record or any other document that explicitly names Isaac’s parents, it’s likely that his father was another Isaac Batten (born 1772), coachman, of Chelsea, and that his mother was called Mary. He also had a younger brother, Charles (1802-1880).(2)

(*That said, there is also a baptism of Isaac Batten, son of Isaac and Mary, in Freshford, Somerset, at the very end of 1789…)(3)

Either way, Isaac certainly had connections to London. Aged twenty-one he married Charlotte Mortimer (1789-1835) at St James’s Church, Paddington, on 30 May 1811.(4) There was an Isaac Batten paying tax in London as late as 1815.(5)

Charlotte & Isaac had six children, all easy to trace thanks to their parents’ distinctive choice of names:

- Alfred Mortimer Batten (1811-1869)

- Mary Anne Charlotte Batten (1817-1893)

- William Wallace Batten (1819-1870)

- Edward Charles Townshend Batten (1821-1895)

- Frederick Adolphus Batten (1823-1826)

- Georgiana Maria Batten (1825-1903)

The first mention of Isaac’s occupation is in 1819 when, while living on Abington Street in Northampton, Charlotte & Isaac Batten, coachman, had their first two children baptised at the church of St Giles in the county town.(6) Their eldest son Alfred had been born in London (Clerkenwell or possibly Marylebone) just before his parents were married – but was baptised in Northampton aged eight.(6,7,8)

The term ‘coachman’ could mean a driver of one of several different classes of vehicle: privately-owned coaches, long-distance stagecoaches, and Hackney carriages. But at the baptism of his third child, Isaac’s job description was more specific: in the register for the parish of Welford, Northants, in 1819, he was recorded as a mail coachman.(9)

⁂

The introduction, thirty-five years earlier, of coaches which carried passengers in addition to the Royal Mail’s deliveries under armed guard, had revolutionised long-distance transport in England. Faster, less crowded, cleaner and safer (though more expensive) than private stagecoaches, the mail coach was the first reliable timetabled public transport service. The coachman – a tough, rough-and-ready, hail-fellow-well-met endurance sportsman, capable of driving through the night at breakneck speed and remaining cheerful throughout – rapidly became a kind of modern folk hero.

There is an excellent sketch description of the ‘coachey’ in The Gentleman’s Pocket Magazine (1827):(10)

“The stage coachman is a careless, jolly dog, in the very nature of whom there is something that smacks, like his own whip, of the dignity of monarchs. He is the elect of the road on which he travels … as he bowls along the road, with rubicund nose, and bang up benjamin [overcoat].

“Listen to the untutored melody of his voice as he preaches the word of exhortation to his tits [horses], and enforces his doctrine with the whip…

“Survey his importance. To some he gives a cool nod; to others a smile of recognition: but thrice happy is he who is honoured with a passing word.

“He has commonly a broad, full face, curiously mottled with red, as if the blood had been forced by hard feeding into every vessel of the skin; he is swelled into jolly dimensions by frequent potations of malt liquors, and his bulk is still further increased by a multiplicity of coats, in which he is buried like a cauliflower, the upper one reaching to his heels. His waistcoat is commonly of some bright colour, striped, and his small-clothes extend far below the knees, to meet a pair of jockey boots which reach about half way up his legs.

“All this costume is maintained with much precision; he has a pride of having his clothes of excellent materials; and, notwithstanding the seeming grossness of his appearance, there is still discernible that neatness and propriety of person, which is almost inherent in an Englishman.

“Every ragamuffin that has a coat to his back, thrusts his hands in the pockets, rolls in his gait, talks slang, and is an embryo coachey.”

– The Gentleman’s Pocket Magazine (London: Joseph Robins, 1827)

There’s some evidence that the compelling composite individual described above was based – at least in part – on my five-greats grandfather. Or, at the very least, that Isaac Batten’s appearance and demeanor fitted the existing stereotype so perfectly that he became the living embodiment of the ‘swell coachman’ and helped to popularise a new stock character in English literature and caricature.

Tony Weller (from Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers) by Joseph Clayton Park (Kyd), 1899. Image in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (More depictions of the veteran coachman and publican can be found on The Victorian Web.)

“COPIED FROM A TOMB-STONE IN A

BURIAL-GROUND NEAR CAMBRIDGE.

“A rum but steady driver,

Quite happy – sans a stiver,

In box-coat e’er attired,

As rough as heart desired.

Sang, drank and smok’d he,

The droll compound us’d to be

Of sense, of nonsense, and of drollery.

Pray for the soul of Isaac Batten,

A worthy dragsman, and a fat ’un.”

– Northampton Mercury, 8 May 1830.

The above poem by an anonymous author was published without comment in a local newspaper, under a title which suggested it had been taken from a real gravestone.(11)

I don’t believe it really was – Isaac Batten was alive and well in 1830 and at the peak of his notoriety, and the humour seems a little coarse and inappropriate for a genuine memorial inscription in the first half of the 19th century. The somewhat puerile rhyme Batten / fat ’un was perhaps too obvious to resist, and it’s telling that essentially the same joke was made in another satrirical poem about well-known coach drivers, written by ‘Rowton’ (pseudonym of some Cambridge wag) and published in another newspaper earlier the same year.(12) I suspect that the ‘tomb-stone’ poem was just a vehicle for a cheap pun on Isaac’s surname and a joke at the expense of his expanse.

(Alternatively, it’s possible that this really was a genuine headstone inscription and that it referred not to the Isaac Batten who was alive in 1830, but to another Isaac Batten – probably his own father – who was also a coachman, and whose burial record has not yet been discovered…)

⁂

It seems that an important part of a coachman’s public persona was the capacity for the intake of impressive amounts of alcohol. Partly this must have been necessary to keep warm on top of a speeding mail coach in the middle of a winter’s night! Partly it must have resulted from their working ungodly hours and taking all of their meals in coaching inns. Partly there seems to have been a sense of pride amongst coachmen in having, and displaying, huge appetites for wine, women, tobacco, roast beef, and song.

There is a memorial to the inevitable result of all this boozing at the reins, on the A40 between Sennybridge and Llandovery in Wales. On the night of 19 December 1835, mail coachman Edward Jenkins – well refreshed after a lightning-quick change of horses at the most recent coaching inn – overturned at full gallop and plummeted down 121 feet of Welsh hillside, his coach smashed to smithereens at the bottom.

Incredibly, no-one was killed or seriously hurt. A memorial pillar was erected in 1841 on the spot of Jenkins’ accident as a permanent warning against intoxication on the turnpike – the world’s first ever anti-drink-driving campaign.(13)

⁂

By the middle of the 1820s, our Isaac Batten and his wife Charlotte had moved from Northamptonshire to the university town of Cambridge and set up home in Brunswick Place (in a fairly well-to-do part of town near Midsummer Common, inhabited by lawyers, solicitors, surgeons and other professionals), where they added three more children to their family.(14–18)

In Cambridge, Isaac became very well known as the driver of ‘The Times’ mail coach which ran the prestigious London-Cambridge route. The Times left Cambridge from the famous Eagle pub on Bene’t Street at 6 o’clock every morning (Sundays excepted), and ran down through Essex via Great Chesterford, Hockerill (Bishop’s Stortford) and Epping, reaching the George and Blue Boar Inn, Holborn, in under seven hours. The return coach left London at 3pm and was expected back in Cambridge by 9 o’clock.(19)

There is an explanation – of sorts – of Isaac’s move from Northampton to Cambridge, in the April 1829 edition of the Sporting Magazine.(20) (I say ‘of sorts’ because it’s written in such dense, late-Regency era sportsman’s slang, full of quotations from the classics, sporting jargon, double entendres, in-jokes, and nose-tap references to obscure people and places, that it’s a bit difficult to determine the exact story.)

It appears that Isaac was operating the ‘Rising Sun’ coach out of Northampton while its usual driver, John Topham, was in the infirmary having broken his leg. When Topham was fit enough to return to the driver’s box, Isaac Batten found himself unemployed. For a while he drove the Cambridge-Fakenham night mail (the ‘Fakenham Ghost‘), before being “brought out of darkness into light… and enthroned upon the bench of the Times, a situation every way calculated to call forth his energies and skill.”(20)

Isaac took over the reins of the Times from another celebrity dragsman called Bob Poynter, “a first-rate artist indeed – who, but for lifting his right hand to excess, must have been there to this day”. In other words, Bob Poynter had fallen victim to the coachman’s occupational hazard – rampant alcoholism.(20)

After Isaac took over the Times, he was supported by a second driver called Fawcett, formerly of the ‘Norwich Day’.(20) Mr Fawcett was a character in his own right: an accomplished classicist, an expert in Latin verse, and fond of shouting out, as he barrelled the Times down Bishopsgate Street, an apocalyptic line from Addison’s Cato:

“Here we go! Amidst the wreck of matter and the crush of worlds!”

– Sporting Magazine, April 1829, p. 418.

The Times was popular with both students of the university and London sportsmen (even Charles Darwin mentions having come down to Cambridge on the Times in a letter in 1829),(21) its drivers Batten and Fawcett quickly gaining a reputation as two of the most skilled and entertaining of the many hell-for-leather dragsmen operating along the Cambridge road.(22)

“EXPEDITIOUS TRAVELLING.—We had an opportunity, last Monday, of comparing the speed of the Cambridge Old Times Coach with that of the Southampton Telegraph, and are bound in fairness, to give the “palm” to the former, which for general appointments, excellence of tits [horses], and superiority of tooling [driving], by the Swell Dragsman, Isaac Batten, exceeds anything we have hitherto witnessed on the road. We left Shoreditch Church at half-past three, drank tea at the Crown, at Hockerell, and arrived at the Eagle, at Cambridge, precisely at nine; thus, doing the whole distance, 58 miles, stoppages included, in five hours and a half.”

– Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 18 March 1827.

Clearly the mail coachmen revelled in excess speed on the highway (and, you suspect, had a fairly cavalier attitude when it came to the safety of other road-users). However, Isaac Batten was careful to appear suitably contrite when in October 1830 he was hauled up in front of Bow Street Magistrates to answer to a charge of furious driving. Racing a fully-loaded Times against another stagecoach for several miles through Essex, Isaac had overturned a gig, injuring its driver. He pleased guilty at once, accepted the magistrate’s warning that next time he could be up on a manslaughter charge, paid the hefty 10-guinea fine there and then, and was on his way.(23)

⁂

Isaac’s wife Charlotte Batten died at her home in Cambridge on 24 March 1835, aged forty-six.(15,24) Isaac carried on as lead driver of the Times for about another five years. The newly-developed railways had begun to carry mail in and out of London in the 1830s, and by the end of that decade the writing was on the wall for the mail coach service, which could not hope to compete with the train on price, speed, capacity, comfort or safety.

While some dragsmen did find employment on the railways, the widowed Isaac Batten followed another well-trodden path for ex-coacheys and took over the licence of an inn. On 2 June 1840, Isaac organised a sale of all his household goods and furniture from Brunswick Place (including his four-poster bed, carpets, tables and chairs, glass and china, his night-commode, and a collection of stuffed birds…)(17) and placed the following advertisement in several local papers:(25)

“QUEEN’S HEAD INN, LITTLEBURY, ESSEX.

“ISAAC BATTEN, (Late coachman to “The Times,”)

“BEGS respectfully to inform the Nobility and Gentry of the University and Town of Cambridge, and those of the county of Essex, and the public in general, that he has taken the above Inn, which is situate near the domain of Lord Braybrooke, and is about 14 miles from Cambridge, hoping by strict attention to their comfort and convenience, combined with moderate charges, to merit a share of their patronage and support.

“N.B.—Dinners ready on the shortest notice, and on the most reasonable terms.

“WINES, of every description, and of the finest quality, good Stabling, Lock-up Coach Houses, and Loose Boxes for Horses.”

– Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 6 June 1840.

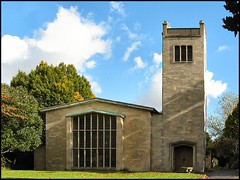

The Queen’s Head in Littlebury near Saffron Walden, Essex, was established in the 15th century and is still going strong in 2016 (www.thequeensheadinn.net). Isaac was clearly trading off his ‘swell’ reputation as a coachman, perhaps hoping to attract some of his former passengers – ideally those with money to spend on fine wines, rich food, and their horses – to his new venture. It’s possible to see a parallel with the late-20th-century cliché of the sports star (maybe an American baseball legend) retiring and opening his own bar where he and his customers can reminisce and relive the glory days. Certainly the Queen’s Head under Isaac Batten became popular with the huntin’ and shootin’ fraternity, and Isaac appears the picture of the genial host, keeping the “toast and song passing freely round” till late into the night.(26)

Queen’s Head Inn, Littlebury, Essex.

© Copyright Dayoff171, all rights reserved.

Three of Isaac’s children – Mary Anne, Charles, and Georgiana – appear in the 1841 census for the parish of Littlebury; the occupation of all three was innkeeper. In the same household was Mary Willmott, aged sixty-seven, also an innkeeper. Isaac himself was not enumerated – where was he on census night? – and a household of only four people seems oddly depleted for a busy coaching inn in June – were there no guests? – no servants or stableboys?(27)

On 12 April 1843, at the age of just fifty-three, Isaac Batten suffered a fatal cerebral apoplexy (i.e. a stroke) at his pub in the village of Littlebury. He was buried back in Cambridge at the Holy Trinity Church, just a couple of streets away from his old coaching base at the Eagle.(1,15,28,29)

It’s tempting to assume that Isaac’s relatively early death was a result of his lifestyle: the alcohol intake; the obesity. However at least one of Isaac & Charlotte’s children also died young of apoplexy – perhaps the Battens were at an increased risk of stroke through some genetic factor.

In the September after Isaac died, his son Charles Batten placed a newspaper advert offering up the lease of the Queen’s Head.(30) The same year an Act of Parliament was passed which paved the way for a railway connection between London and Cambridge. The heyday of the mail coach was over, though the speed and flair of the Times and her driver would be fondly remembered by those who had travelled in her:

“MANY must still be living who can remember those good ‘old coaching days,’ when the box-seat of a well-appointed conveyance was considered one of the most enviable of places, and when the coachman happened to be popular, and would hand over the ‘ribbons’ to some ‘gentleman dragsman,’ fresh from Oxford or Cambridge. Many a five-shilling piece, or even a sovereign, was his reward for endangering his passengers’ lives.

“To go back some forty years, when two of the best-appointed coaches of the day, the ‘Times Cambridge,’ and the ‘Cambridge Fly,’ one driven by Batten, the other by Fawcett, both celebrated men of that day. It is of the ‘Times’ we have to speak. On its panels was written ‘Tempus fugit;’‡ by no means wrongly applied, for the journey from London to Cambridge, fifty-three miles, was completed within five hours; and it performed the wonderful feat, when running opposition to the ‘Fly,’ of changing horses and driving in and out the yard, of that (in those good old times) celebrated inn Epping Place, in the all but incredible space of one minute! These were pleasant days, gone, alas! never to return.

(‡Tempus fugit – ‘The Times flies’ – another pun.)

– Baily’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, 1881, vol. XXXVI, p. 34.

Illustration of the Louth to London mail coach

being loaded on to the back of a train, pre-1845.

© Copyright The Postal Museum, all rights reserved.

⁂

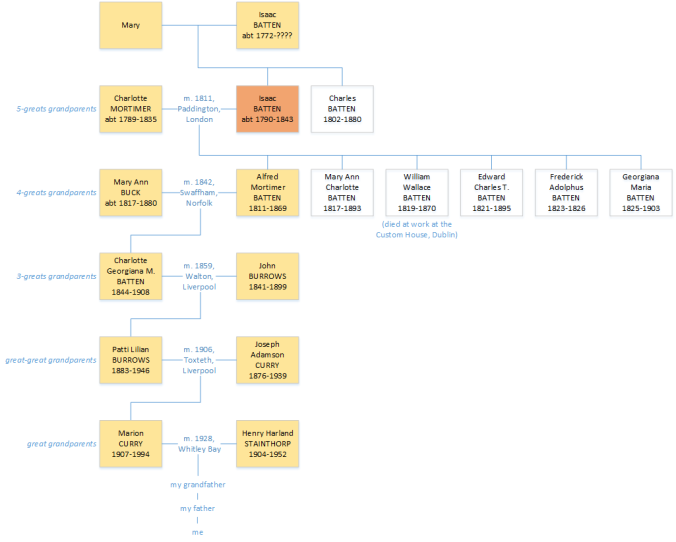

Isaac Batten’s eldest child, my four-greats grandfather Alfred Mortimer Batten, was born in London (Clerkenwell or Marylebone) on 23 April 1811, but baptised in Northampton at the age of eight.(6,7,8)

On 16 November 1842 in Swaffham, Norfolk, Alfred married farmer’s daughter Mary Ann Buck:32 they had nine children. At first, living in Brandon on the Norfolk/Suffolk border, Alfred, following in his father’s footsteps, was a coachman – then, like many recently-redundant coacheys he found work as a railway guard, in London. Around 1855, Alfred and his growing family moved north to Liverpool, where in another change of career he became a pawnbroker. He was presumably supported in this by his uncle, Isaac Batten’s brother Charles, who was already in that trade in Liverpool.(7,8)

Alfred M. Batten died at his home in Ashton Street, Liverpool, on 15 March 1869; he is buried in Toxteth Park Cemetery.(1,33,34) Alfred’s own eldest child, my three-greats grandmother, was named Charlotte Georgiana Maria Batten after her grandmother and aunt. She married wholesale clothier John Burrows in 1859; the couple lied on the marriage register to cover up the fact that Charlotte was barely fifteen years old.(35)

Charlotte & John Burrows had a large family – twelve children including my great-great grandmother, Patti Lilian Burrows;(36) Patti’s daughter Marion Curry married master butcher Henry Harland Stainthorp in 1928.(35)

Sketch family tree showing my descent from Isaac Batten & Charlotte Mortimer.

Click on the image for a larger version.

Of Charlotte & Isaac Batten’s other five children:

Mary Anne Charlotte Batten was born in Northampton on 17 November 1817 and baptised there just before her second birthday.(6) She was recorded in the 1841 census as an innkeeper in Littlebury.(27) Two years later, shortly after the death of her father, she married a barrister, William Beresford, who became a county court judge in Carmarthenshire.(34,37) She died in 1893 in Machynlleth registration district.(38)

Kelsboro Ware coachman Toby Jug, 1950s. “In box-coat e’er attired,

As rough as heart desired.”

William Wallace Batten was born and baptised in Welford, Northamptonshire, at the end of 1819.(9) On 15 January 1839, aged nineteen, he entered into service with Her Majesty’s Board of Excise and was posted to Ireland.(18) He married twice and had four daughters.(39) (One small oddity: at both of his marriages in Ireland, William’s father’s name is recorded as Isaac Smith Batten. Where did the ‘Smith’ come from? Isaac has no middle name on any other record he appears in.) On 2 July 1870, at his desk in the Custom House, Dublin, William Batten suddenly fell backwards without uttering a word, dead of apoplexy at fifty years old. He is buried at Mount Jerome Cemetery, Dublin.(39–42)

Edward Charles Townshend Batten, known as Charles. Born in London on 18 September 1821,(7) he was baptised at the church of St Andrew the Less, Cambridge, in January 1828 aged six.(14) He was recorded in the 1841 census as an innkeeper in Littlebury.(27) Along with his uncle Charles and brother Alfred, Charles Batten was a pawnbroker in Liverpool.(7) He married twice and died in Eastcote, Northamptonshire, on 6 September 1895.(36,43)

Frederick Adolphus Batten was born in 1823 in Cambridge. He died shortly before his third birthday.(14,15)

Georgiana Maria Batten, born in Cambridge on 18 November 1825. For some reason she was baptised twice at the same church (St Andrew the Less, Cambridge) – once in December in the year of her birth, then again in January 1828 alongside her elder brother Charles.(14) She was recorded in the 1841 census as an innkeeper in Littlebury.(27) She married twice and had two daughters; both sadly died in childhood. Georgiana herself died in Southport registration district on 10 September 1903 and was buried in Toxteth Park Cemetery in Liverpool.(34,36)

⁂

I would like to thank a distant cousin T. F. C. Batten whose own research established the link between Isaac Batten of Northampton/Cambridge and his likely parents Isaac and Mary in London; also for the fantastic and generous hoard of digitised documents, articles, and ideas. Thanks also to the members of the RootsChat family history forum for suggestions for further research.

Paul Harland Stainthorp (paul@paulstainthorp.com).

Version 1.2, updated 18 November 2017.

⁂

References

- England and Wales, death certificate (certified copy); General Register Office, Southport.

- Personal e-mail; privately held by the author.

- “FreeReg,” database, FreeReg (http://www.freereg.org.uk/ : accessed 2 September 2016).

- St James’ Church (Paddington, London, England), parish registers; digital images, Ancestry Library Edition (http://www.ancestrylibrary.com/ : accessed 2 October 2015).

- “London, England, Land Tax Records, 1692-1932,” digital images, Ancestry Library Edition (http://www.ancestrylibrary.com/ : accessed 29 June 2016); London Metropolitan Archives.

- St Giles’ Church (Northampton, Northamptonshire, England), parish registers; digital images.

- “1851 England Census,” digital images, Ancestry Library Edition (http://www.ancestrylibrary.com/ : accessed 18 December 2015); The National Archives, Kew.

- “1861 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- St Mary’s Church (Welford, Northamptonshire, England), parish registers.

- The Gentleman’s Pocket Magazine; and album of literature and fine arts (London: Joseph Robins, 1827); digital images, Hathi Trust (https://babel.hathitrust.org/ : accessed 9 May 2016).

- Northampton Mercury, 8 May 1830.

- Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 17 January 1830.

- Watkins, Graham, Mail coach monument, 8 March 2011 (http://www.grahamwatkins.info/ : accessed 26 September 2016).

- “Cambridgeshire Baptisms,” database, Findmypast (http://www.findmypast.co.uk/ : accessed 23 May 2016); Cambridgeshire Family History Society.

- “Cambridgeshire Burials,” database; Cambridgeshire Family History Society.

- “UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893,” digital images, Ancestry Library Edition (http://www.ancestrylibrary.com/ : accessed 19 December 2015); London Metropolitan Archives and Guildhall Library.

- Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, and Huntingdonshire Gazette, 30 May 1840.

- William Wallace Batten. Entry papers for service as an Excise man. The National Archives, Kew, ref. CUST 116/6/21.

- The Cambridge University calendar for the year 1829 (printed by J. Smith for J. & J.J. Deighton, 1829).

- Sporting Magazine, April 1829, vol. XXIII N.S., no. CXXXIX, pp. 414-419.

- Larkham, Anthony W. D., A natural calling: life, letters and diaries of Charles Darwin and William Darwin Fox (Springer, 2009)

- Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 18 March 1827.

- Courier [London], 23 October 1830.

- Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, and Huntingdonshire Gazette, 27 March 1835.

- ibid., 6 June 1840.

- Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 21 March 1841.

- “1841 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, and Huntingdonshire Gazette, 15 April 1843.

- Essex Standard and General Advertiser [Colchester], 21 April 1843.

- Chelmsford Chronicle, 1 September 1843.

- Baily’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, 1881, vol. XXXVI, p. 34.

- Church of St Peter and St Paul (Swaffham, Norfolk, England), parish registers; digital images, Findmypast (http://www.findmypast.co.uk/ : accessed 26 September 2016).

- Liverpool Mercury, 20 March 1869, p. 5.

- Anderson, Robert and Anderson, Rose, Toxteth Park Municipal Cemetery inscriptions (http://www.toxtethparkcemeteryinscriptions.co.uk/ : accessed 3 October 2015).

- England and Wales, marriage certificate (certified copy); General Register Office, Southport.

- “1891 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- St Luke’s Church (Chelsea, London, England), parish registers; digital images.

- “FreeBMD,” digital images, FreeBMD (http://www.freebmd.org.uk/ : accessed 29 March 2016); General Register Office, Southport.

- Ireland, Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs, “Civil Records,” digital images, Irish Genealogy (https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/ : accessed 2 October 2016).

- Evening Freeman [Dublin], 4 July 1870.

- “Calendars of Wills and Administrations 1858 – 1920,” digital images, The National Archives of Ireland (http://www.willcalendars.nationalarchives.ie/ : accessed 2 October 2016).

- “Dublin Headstones,” digital images, Ireland Genealogy Projects Archives (http://www.igp-web.com/IGPArchives/ire/dublin/photos/tombstones/ : accessed 1 October 2015).

- “Find a will: Wills and Probate 1858 – 1996,” digital images, Gov.UK (https://probatesearch.service.gov.uk/ : accessed 1 July 2015); National Probate Calendar.

Eva (1896-1957) – born 12 February, Lincoln. Married Harry Bunn, 1923, Lincoln; one son (Maurice) who died in infancy. Worked as a housekeeper in Lincoln.

Eva (1896-1957) – born 12 February, Lincoln. Married Harry Bunn, 1923, Lincoln; one son (Maurice) who died in infancy. Worked as a housekeeper in Lincoln. Dora Annie (1906-1984) – born 13 October, Lincoln. Married millworker John Thomas (“Tom”) Foster, 1935, Lincoln; one son. Lived at 68 Goldsmith Walk. Died 12 June 1984, Lincoln St George’s Hospital.

Dora Annie (1906-1984) – born 13 October, Lincoln. Married millworker John Thomas (“Tom”) Foster, 1935, Lincoln; one son. Lived at 68 Goldsmith Walk. Died 12 June 1984, Lincoln St George’s Hospital.