I’m writing up my notes about my wife’s ancestors the Black family of Lincolnshire for a relative who is visiting England next year.

John Black & Eleanor Martin

The story begins in 1773, in the Lincolnshire village of Carlton-le-Moorland, half way between the market town of Newark-on-Trent and the city of Lincoln, with the birth of a child. On 7 March that year, a girl was baptised in Carlton at the village church of St Mary’s, her name entered into the register as:

Black mark – the mark of John Black

“of Doncaster in the County of York“, his marriage bond, 11 March 1773. Reproduced from the original held at Lincolnshire Archives.

“Fanny, Illegitimate Dr of John Black & E. Martin”.1

Four days later, no doubt under pressure from the Martin family and from the church, the girl’s father John Black obtained a marriage bond from the Diocese of Lincoln: this allowed him to marry Eleanor Martin on 12 March 1773 in Carlton-le-Moorland without the usual reading of Banns… on pain of forfeiting £200 to the diocese if the marriage turned out not to be valid.1,2

(Spelling being much more variable in the 18th century than it is today, Eleanor Martin’s name was sometimes written as “Hellen”, and she herself signed the marriage register using the spelling “Ellner”. John Black made an “X”.)1

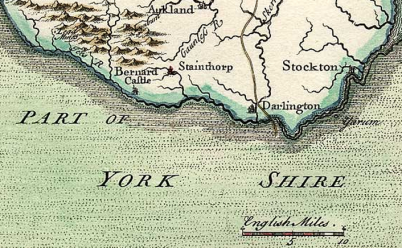

While Eleanor was resident in the parish of Carlton-le-Moorland, John Black had come from Doncaster in Yorkshire, forty-odd miles to the north. Like most working men in England in the time before the industrial revolution, John was an agricultural labourer.

After they were married, John and Eleanor had two sons in Carlton:1

- George (1780)

- William (1784)

John Black died in Carlton-le-Moorland in 1803. He was 57 years old when he died, which places his birth around the year 1746.1 I haven’t yet traced John’s early life in Doncaster before he came to Lincolnshire. He may have been born and baptised there, or like many agricultural labourers he may have moved from parish to parish, securing work at annual hiring fairs before eventually settling down.

William Black & Ann Eato

At some point before or following the death of John Black, his family moved to the village of Waddington, eight miles from Carlton-le-Moorland on the road to Lincoln. I haven’t been able to find out what happened to Eleanor and John’s first child – their daughter Fanny – but their two sons George and William Black both became successful farmers in Waddington. (Eleanor herself died in Waddington in 1827 at the age of 82 and was buried back in her home village of Carlton-le-Moorland.)1

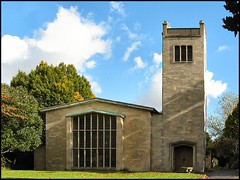

The elder son George married Mary Hammond on 16 May 1809 at the old parish church of St Michael in Waddington.3 (This old twelfth-century church no longer exists – it was destroyed on the night of 8 May 1941 by a bomb intended for the nearby RAF base.)4 George and Mary had two sons (George and John); the family farmed land on the manor of Mere Hospital, east of the village of Waddington though now cut off from it by the huge airbase at RAF Waddington. George Black died in November 1846.3,5

The new St Michael’s Church, Waddington, built in 1954 as a replacement for the twelfth-century church destroyed during WWII.

© Copyright Brian and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

John and Mary’s younger son William married Ann Eato on 17 May 1821 in Waddington. “Eato” is an unusual old East Midlands surname subject to more than the usual amount of spelling variation – for example on William and Ann’s entry in the marriage register it is spelt “Aitoo”.3

Ordnance Survey six-inch map

of Waddington and Mere, 1887,

showing the manor of Mere Hospital.

National Library of Scotland.

- Eleanor [or El(l)en, or Helena!] (1822)

- William (1825)

- Joseph (1826)

- Mary (1828)

- John (1830)

- George I (1832 – died in infancy)

- George II (1833)

- Ann (1837 – died in infancy)

By now you will have spotted the repetition of names across the last two generations. This seems to be a particular feature of the Black family – until the early 20th century they were very conservative in following the traditional practice of naming sons after fathers, uncles and grandfathers; daughters after mothers, aunts and grandmothers. All families did this to a certain extent, but in farming families like the Blacks the custom seems to have been followed rigidly. It can make it difficult to trace individuals when, for example, there are four George Blacks on the go in the same village at the same time…

William and Mary Black, with two of their six surviving children, appear in the 1851 census of England in the parish of Waddington. William – aged 66 and born in Carlton-le-Moorland – is listed as a cottager or smallholding farmer of 8½ acres – this is the land the Blacks were known to farm at Mere Hospital.7

When William died on 17 May 1856 he was 71 years old. In his will, proved at the Consistory Court of Lincoln on 6 June that year, William specified that the 8½ acres of copyhold land he held of the manor of Mere Hospital be made available for the use of his wife Ann for the rest of her life or until she remarried, then divided amongst their six living children (sons William, Joseph, John and George; daughters Elen and Mary).8 William’s wife Ann Black née Eato died one year after her husband, in June 1857.3

All of William and Ann’s children lived out their entire lives in rural Lincolnshire – except one. Their youngest son George Black (born in 1833) – named after an older sibling who sadly lived for less than a fortnight – was apprenticed to a joiner in his home village, but left Lincolnshire for the Chorlton area of industrial Manchester, where he became a beer retailer.7,9 He died in Manchester in 1868.10,11

William Black & Mary Robinson

William Black’s second child and eldest son with his wife Ann was named William Black after his father.

William the younger was baptised at Waddington St Michael’s on 1 May 1825.3 This William was born at a time of agricultural revolution in England, as a wide variety of new machinery was developed and new efficient methods of farming introduced. By the time William senior died in 1856, the proportion of the British population working in agriculture was under 22% – lower than in any other country in the world.12

On 8 July 1851 – three months after he was enumerated on the 1851 census as an agricultural labourer, living with his parents in Waddington – William Black married Mary Robinson at her home parish church of All Saints, Nettleham.13 Mary’s parents were William Robinson and Jane Clayton. The Robinsons were originally from Rampton in Nottinghamshire but had been living in Nettleham since the 1820s.7,13

The signatures of William Black & Mary Robinson,

from the parish register entry for their marriage, 1851.

Reproduced from microfilm held at Lincolnshire Archives.13

- Ann (1855 – died aged 15)

- William (1858)

- Mary (1860)

- Ada (1869 – died in infancy)

After his mother’s death in 1857, William junior had inherited a part of his father’s land in the manor of Mere Hospital.8 By 1861 he had added to these 8½ acres, being recorded as cottager of 20 acres of land. (Yet more of the Mere Hospital land was being farmed by William’s siblings and Black cousins.)9

William died on 26 August 1872.3,10,11 The executors of his estate – his widow Mary and brother Joseph – arranged a public sale of the Mere Hospital copyhold land, at the Horse and Jockey Inn in Waddington on 24 October 1872.11,14 This sale of the land seems slightly strange to me: why didn’t the copyhold pass to William’s only son – who certainly carried on farming – and/or his only surviving daughter Mary? William’s probate file – which could be ordered from the UK Find a will service – may hold the answer.11

Horse and Jockey Inn, Waddington, Lincs., where William Black’s land was sold in 1872.

© Copyright Brian and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

William’s widow Mary was still living in Waddington in 1881. She was recorded as being of independent means: perhaps she was still living off the profits of the sale, eight years earlier, of her late husband’s land. With her was her son William, aged 23 and a farmer.15 Three years later her daughter Mary, who had been working as a cook in service at Usselby Hall,15 married coachman Edward Barnes.16 The couple moved to Coleby, the next-but-one village south of Waddington, and the widowed Mary Black moved in with her daughter and son-in-law: she died in 1891 shortly after the census was taken.3,17

William Black & Mary Pask

William Black, the third generation to hold that name, was born on 7 February 1858 in Waddington.3,10,18

William III grew up in Waddington, the son of a farmer and later a farmer in his own right. For some reason he did not inherit his father’s land at Mere Hospital manor, which was sold in 1872.14

Photograph of (back row) Mary Black née Pask,

William Black?, “Eva” with unnamed baby,

(front row) “Tom” (Spicer?), Rebecca Pask née Mabbott,

at the latter’s home in Boothby Graffoe, before 1934.

Family photograph, © all rights reserved.

Mary Pask, the daughter of master cordwainer (shoemaker) William Pask and his wife Rebecca née Mabbott, was born in the village of Navenby on 9 March 1864 but grew up in nearby Welbourn before going into domestic service.10,15,18

The surname “Pask” is another unusual and interesting one, deriving from the Norman-French Pasque meaning ‘Easter’, and ultimately from Hebrew פֶּסַח (Pesach) – Passover. There is a long-running and comprehensive one-name study of the Pask families of Lincolnshire and elsewhere, with a website at: www.pask.org.uk

By the time of her marriage to William Black in 1885, Mary’s parents had moved to Boothby Graffoe, not far from William’s home village.15 Her mother Rebecca Pask (née Mabbott) is at the centre of a family photograph taken probably around the time of her 90th birthday. In it, Rebecca (born 1842), wearing very Victorian-looking black, is seated in her garden at Boothby Graffoe surrounded by members of her family including her daughter Mary and probably her son-in-law William Black. She is certainly the earliest person in my family tree that I have a photo of.

William and Mary Black née Pask left Waddington around the year 1887. Initially they moved into the West End of the city of Lincoln where William worked as a general labourer.17,20 Following this, the family spend several years moving from village to village (Burton in 1901; Nettleham in 1902; Skellingthorpe in 1903) where William did a series of agricultural jobs – these moves are reflected in the varied birthplaces of their children.21–25

By 1906 the Black family were back in Lincoln, settling down at number 35, Hope Street, near the corner with Norris Street, in the south of the city very near the Cowpaddle common.24,25,26

William and Mary had a large family – the largest in my family history software – of fourteen children:

- Jennie (1885-1971) – born 8 December, Waddington. Worked as a domestic servant for George John Bennett, noted composer and organist of Lincoln Cathedral. Had a son, Robert Sydney (“Bob”) Black in 1913. Married building contractor Albert E. Donson, 1936, Lincoln; they lived at her parents’ old house, 35 Hope Street.10,18,25,27

- William “Jack” (1887-1972) – born 5 February, Waddington. Emigrated to Australia; married Aletha May Eggins, 26 May 1915, Sydney. Lived at 443 Cabramatta Road, Liverpool, New South Wales; worked as a railway employee.10,18,28,29,30

- Ada (1888-1948) – born 16 November, Lincoln. Married fish dealer Naaman Spicer, 19 December 1910, St Andrew’s Church, Lincoln. Lived in Long Bennington, Lincolnshire and Stanton Hill, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire. Eight children including two sons who emigrated to the Canadian province of British Columbia.10,18,25,27,31

George Mabbott (1890-1915) – born 30 November, Sturton by Stow. Worked as a farm waggoner and foundry machine hand. Joined the Royal Navy in 1914 as a stoker. Died of dysentery on board HMS Wolverine, Aegean Sea, 27 August 1915; memorialised at East Mudros Military Cemetery, Lemnos (Λήμνος), Greece.10,18,25,32,33,34

George Mabbott (1890-1915) – born 30 November, Sturton by Stow. Worked as a farm waggoner and foundry machine hand. Joined the Royal Navy in 1914 as a stoker. Died of dysentery on board HMS Wolverine, Aegean Sea, 27 August 1915; memorialised at East Mudros Military Cemetery, Lemnos (Λήμνος), Greece.10,18,25,32,33,34- Amy (1893 – died in infancy)

- Alice (1894 – died in infancy)

Eva (1896-1957) – born 12 February, Lincoln. Married Harry Bunn, 1923, Lincoln; one son (Maurice) who died in infancy. Worked as a housekeeper in Lincoln.10,18,25,27

Eva (1896-1957) – born 12 February, Lincoln. Married Harry Bunn, 1923, Lincoln; one son (Maurice) who died in infancy. Worked as a housekeeper in Lincoln.10,18,25,27- Arthur (1897-1915) – born 2 May, Lincoln. Worked as a butcher at a shop in Sincil Street, Lincoln. Joined the 4th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment in 1914. Killed in action in the battle of the Hohenzollern Redoubt, 13 October 1915; his name is recorded on the Loos Memorial.10,18,25,34,35

- Fred (1899-1991) – born 17 August, Lincoln. Joined the Royal Navy in 1921; also served three years with the New Zealand Navy from 1926. Married Violet G. Goodenough, 1922, Kingston, Surrey; seven children. Lived in Portsmouth.10,18,25,32,36

- Harry (1901-1986) – born 31 October, Burton. Married Annie Goy in 1928 in Timberland; five children. Lived on Fen Lane, Timberland; worked as a general labourer.10,18,25,27,36

- John Victor (1903-1975) – born 6 May, Skellingthorpe. Married Elsie May Cullen, 1939, Lincoln. Lived at 14 Palmer Street, Lincoln; worked as a railway shunter.10,18,25,27,36

- Elsie Mary (1904-1987) – born 7 December, Nettleham. Lived in Southsea, Hampshire; worked as a cook. Married Stephen Dudley Doust, 1940, Portsmouth; three children.10,18,25,27,36

Dora Annie (1906-1984) – born 13 October, Lincoln. Married millworker John Thomas (“Tom”) Foster, 1935, Lincoln; one son. Lived at 68 Goldsmith Walk. Died 12 June 1984, Lincoln St George’s Hospital.10,18,25,27,36,37

Dora Annie (1906-1984) – born 13 October, Lincoln. Married millworker John Thomas (“Tom”) Foster, 1935, Lincoln; one son. Lived at 68 Goldsmith Walk. Died 12 June 1984, Lincoln St George’s Hospital.10,18,25,27,36,37- Cyril Stanley (1908-1974) – born 28 May, Lincoln. Lived in Timberland; worked as a roadman. Married Mabel Barrand, 1940, Timberland; one son.10,18,25,27

I’ve written elsewhere about the brothers George Mabbott Black and Arthur Black, both of whom were killed in the First World War – one by disease and one by enemy action. Since that original post I have been sent a copy of a newspaper article from 1915 which reported that the younger of the two brothers, Bugler Arthur Black of 4th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment, had been reported missing in action. The article includes part of a letter of sympathy and reassurance written by Arthur’s comrade – and fellow Lincoln resident – Signaller George Crosby, to Arthur’s mother Mary Black:35

On Tuesday, 13 October 2015, the centenary of the battle which killed Arthur Black, the bells of St Mary-le-Wigford in the centre of the city of Lincoln rang out half-muffled.

The names of the men killed on that day were placed on a board outside the church.

“I will enquire all over, every day, until I do hear of him…

It was terrible that day. Hundreds seemed to fall, and to see them falling, to rise no more, by our side, sent us all mad…

Mrs Black, if the worst has happened, you can take it from me that he died a hero, and I am proud to be a pal of his.”– Lincolnshire Chronicle, 20 November 1915.

Arthur Black was killed on 13 October 1915 in the battle of the Hohenzollern Redoubt, when 357 soldiers of the 1/4th and 1/5th Lincolnshire Regiment died in less than half an hour along with a thousand other men. 90% of them – Arthur Black included – have no known grave.

⁂

William Black died at his home at 35 Hope Street, Lincoln, on 16 November 1938. He was eighty years old.10,26

His widow Mary moved out to the village of Timberland, fourteen miles south-east of Lincoln in the Witham Fen, to be near her sons Harry and Cyril Black; she died there in August 1939 after a short illness.10 Her funeral was attended by nine of her ten surviving children (only William, in Australia, could not be there) and by dozens of members of the extended family.38

Mary Black née Pask.

Family photograph, © all rights reserved.

⁂

Particular thanks are due to the staff of Lincolnshire Archives, to Stuart and Teresa Pask of the Pask, Paske one-name study website, and to E. Baglo for information, interest and photos.

Paul Harland Stainthorp (paul@paulstainthorp.com). Version 1.0, updated 20 September 2016.

⁂

References

- St Mary’s Church (Carlton-le-Moorland, Lincolnshire, England), parish registers; digital images, Lincs to the Past (http://www.lincstothepast.com/ : accessed 29 August 2016).

- Diocese of Lincoln, marriage bond, ref. MB 1773/449, John Black, 11 March 1773; Lincolnshire Archives, Lincoln.

- St Michael’s Church (Waddington, Lincolnshire, England), parish registers; digital images.

- Miller, Terry and Towers, Jean, Waddington at war 1939-1941 (Waddington Local History Group, 1992).

- Lincoln Consistory Court, will and probate, George Black (d. before 3 Nov 1846), ref. LCC WILLS/1846/47; Lincolnshire Archives, Lincoln.

- All Saints’ Church (Wellingore, Lincolnshire, England), parish registers; digital images.

- “1851 England Census,” digital images, Ancestry Library Edition (http://www.ancestrylibrary.com/ : accessed 18 December 2015); The National Archives, Kew.

- Lincoln Consistory Court, will and probate, William Black (d. 17 May 1856), ref. LCC WILLS/1856/38; Lincolnshire Archives, Lincoln.

- “1861 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- “FreeBMD,” digital images, FreeBMD (http://www.freebmd.org.uk/ : accessed 29 March 2016); General Register Office, Southport.

- “Find a will: Wills and Probate 1858 – 1996,” digital images, Gov.UK (https://probatesearch.service.gov.uk/ : accessed 1 July 2015); National Probate Calendar.

- Overton, Mark, ‘Agricultural revolution in England 1500 – 1850,’ BBC – History, 17 February 2011 (http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ : accessed 15 September 2016).

- All Saints’ Church (Nettleham, Lincolnshire, England), parish registers; Lincolnshire Archives, Lincoln.

- Stamford Mercury, 11 October 1872, p. 2.

- “1881 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- St Michael’s Church (Waddington, Lincolnshire, England), parish registers; Lincolnshire Archives, Lincoln.

- “1891 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- “Birth-Day Greetings”, birthday diary, printed circa 1900; family artefacts; privately held by the author.

- Lincolnshire Chronicle, 24 July 1885, p. 5.

- Church of St Mary-le-Wigford (Lincoln), parish registers; digital images.

- “1901 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- “FreeReg,” database, FreeReg (http://www.freereg.org.uk/ : accessed 2 September 2016).

- St Lawrence’s Church (Skellingthorpe, Lincolnshire, England), parish registers; digital images.

- St Andrew’s Church (Lincoln, Lincolnshire, England), parish registers; digital images.

- “1911 England Census,” digital images; The National Archives, Kew.

- Lincolnshire Echo, 17 November 1938, p. 1.

- “1939 Register,” digital images, Findmypast (http://www.findmypast.co.uk/ : accessed 3 March 2016); The National Archives, Kew.

- State of New South Wales, “Births, Deaths and Marriages search,” database, Registry of Births Deaths & Marriages (https://familyhistory.bdm.nsw.gov.au/ : accessed 23 July 2016).

- Clarence & Richmond Examiner, 5 June 1915, p. 1.

- “Australia, Electoral Rolls, 1903-1980,” digital images, Ancestry Library Edition (http://www.ancestrylibrary.com/ : accessed 28 December 2015); Australian Electoral Commission.

- Personal e-mail; privately held by the author.

- “British Royal Navy Seamen 1899-1924,” digital images, Findmypast (http://www.findmypast.co.uk/ : accessed 31 August 2016); The National Archives, Kew.

- Lincolnshire Chronicle, 4 September 1915, p. 1.

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission, “Find War Dead,” digital images, CWGC (http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/ : accessed 1 April 2015).

- Lincolnshire Chronicle, 20 November 1915, p. 5.

- “England and Wales Death Registration Index 1837-2007,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ : accessed 12 July 2016); General Register Office, Southport.

- Lincolnshire Echo, 13 June 1984, p. 10.

- “The Death took place of Mrs. Mary Black…,” undated cutting, about 1939, from unidentified newspaper; family artefacts; privately held by the author.